"I will put my law in their minds and write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people."

--Jeremiah 31:33 (NIV)

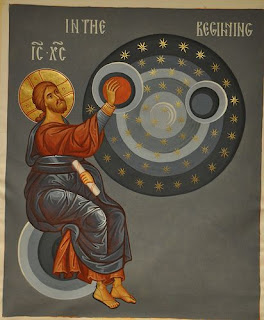

The historical relationship between the Christian and the state has always been a case of curiosity. This is all the more exemplified when we see around us those self-proclaimed followers of Christ trying to bring about the kingdom of God through mimetic games designed by the state priesthood. This effort of blending two religions (one centered around Christ mimesis and the other centered on the imitation of man) together is an exercise in futility. The truth is that the incarnation paves the way for the destruction of governments on a worldwide scale. Some two thousand years ago, a babe born into an obscure middle-eastern town heralded the coming of God's kingdom and the death of empires and government. The life that came out from the virgin would destroy governments once and for all, but this destruction would come only through the viral imitation of that very life itself.

In Victor Hugo's novel 'Les Misérables' we can see how imitation of Christ leads to a contagion of God's love through individuals that ultimately affects society at large. Jean Valjean is a former convict who is shown mercy by an old priest when he is caught stealing. This act of compassion from the priest amazes Valjean so much that the criminal decides to embrace the forgiving priest as his new model. By embracing the priest as his model for imitation, Valjean has effectively chosen to imitate Christ; he is now the Christ-man. As a result of his decision, Jean Valjean rises up to become the mayor of a small town through nothing but small yet significant acts of charity and kindness. He is always helping the needy and downtrodden, and he is always humble and discreet in his actions. Soon however, his very existence is thrown up for grabs with the entrance of the zealot police inspector Javert, who wishes to exert the full force of the law upon Valjean's town, even if it means throwing reformed men into cages like animals for past sins. In more simple terms, Javert is the spirit of the accuser, more aptly described in scripture as Satan.

One day, inspector Javert comes across a wretched prostitute who has just struck a man in self defense. Javert commands his men to have the prostitute thrown in jail. He ignores the prostitute's pleas of mercy and is ruthless with his decision, but in comes Valjean, who exercises his much superior authority and pardons the prostitute. Valjean even goes as far as to medically treat the prostitute when she is dying, and he promises to take care of the prostitute's daughter. This throws Javert and Valjean into a head-on collision course. The eventual unmasking of Valjean as an ex-convict causes Valjean to flee with the prostitute's daughter. But Javert will not stop in his pursuit of justice, and he chases Valjean across the country.

Javert is the personification of the state. He is the state's high priest. His unquenchable desire to uphold the law is revealed to be ancient in origin and, hence, sacrificial. Today, many intellectuals speak of the violence of religion, yet very few speak of the violence of the state. The state is very religious, not many dare to recognize this. It operates through the ancient but effective sacrificial mechanism. Scapegoats, violent and non violent offenders, are routinely thrown into cages by the priesthood; this keeps the state in existence, and the catharsis just balmy enough to contain a full fledged all-against-all war. Valjean, on the other hand, is the Christ imitator. He is a priest of the kingdom of God. He is chained to Christ mimesis, and thus cannot use violence and coercion. His only weapon is the crucified life of Christ.

Whereas Javert does not care about a man's potential to reform, Valjean forgives freely. Javert is the law through coercion while Valjean is the law through imitation. One mercilessly throws human beings into cages and the other turns the cheek. The two are, for obvious reasons, irreconcilable.

Javert is finally able to apprehend his man after years of pursuit, but he realizes the superiority of Valjean's law and concludes that he is made directionless because of Valjean's Christ-man. He realizes the immorality of the state's use of violence and the brutal nature of its prisons where countless men languish and are broken forever. The inspector lets go of his man, and commits suicide, marking the obsolete nature of the state in the presence of a viral Christian mimesis.

To this day, thousands suffer in prison. The state-engineered media will echo the violence committed by people, but it will always downplay the violence of the state. Little is spoken of the widespread rape of offenders in prisons across the world. A man guilty of not paying back loans is just as likely to be raped as the vicious murderer. And all this while under the supervision of the state's priesthood. This is the cold reality of governments everywhere.

The state has always been a continuation of religion; violence and coercion has always been it's ritual sacrifice. But this does not mean that we should rise up and rebel against it in a mimetic manner. Such stupidity is reserved for the Marxists and clueless leftists. God revealed to us what we must do while living under the state. His answer is Jesus. This answer is amplified in Victor's Hugo's Jean Valjean. The ex-convict Valjean shows mercy not only to the victims, but also to the oppressors. His form of justice is restorative and does not require scapegoats. He helps out the workers. He practices benevolence towards those who are unfortunate enough in society. He becomes father and protector to an orphaned girl. And he, on more than one occasion, spares Javert's life.

The life of the fictional Valjean is a mirror image of the divine Savior. His life is an excellent example of how Christians must behave under the tyranny of the state. Only a fool would take the state, which makes full use of the scapegoat mechanism, as a moral agent of society. The true moral agent for mankind is and has always been none other than Jesus Christ, and his imitation, and the viral nature of it, renders all government and religious institutions obsolete.

--Jeremiah 31:33 (NIV)

The historical relationship between the Christian and the state has always been a case of curiosity. This is all the more exemplified when we see around us those self-proclaimed followers of Christ trying to bring about the kingdom of God through mimetic games designed by the state priesthood. This effort of blending two religions (one centered around Christ mimesis and the other centered on the imitation of man) together is an exercise in futility. The truth is that the incarnation paves the way for the destruction of governments on a worldwide scale. Some two thousand years ago, a babe born into an obscure middle-eastern town heralded the coming of God's kingdom and the death of empires and government. The life that came out from the virgin would destroy governments once and for all, but this destruction would come only through the viral imitation of that very life itself.

In Victor Hugo's novel 'Les Misérables' we can see how imitation of Christ leads to a contagion of God's love through individuals that ultimately affects society at large. Jean Valjean is a former convict who is shown mercy by an old priest when he is caught stealing. This act of compassion from the priest amazes Valjean so much that the criminal decides to embrace the forgiving priest as his new model. By embracing the priest as his model for imitation, Valjean has effectively chosen to imitate Christ; he is now the Christ-man. As a result of his decision, Jean Valjean rises up to become the mayor of a small town through nothing but small yet significant acts of charity and kindness. He is always helping the needy and downtrodden, and he is always humble and discreet in his actions. Soon however, his very existence is thrown up for grabs with the entrance of the zealot police inspector Javert, who wishes to exert the full force of the law upon Valjean's town, even if it means throwing reformed men into cages like animals for past sins. In more simple terms, Javert is the spirit of the accuser, more aptly described in scripture as Satan.

One day, inspector Javert comes across a wretched prostitute who has just struck a man in self defense. Javert commands his men to have the prostitute thrown in jail. He ignores the prostitute's pleas of mercy and is ruthless with his decision, but in comes Valjean, who exercises his much superior authority and pardons the prostitute. Valjean even goes as far as to medically treat the prostitute when she is dying, and he promises to take care of the prostitute's daughter. This throws Javert and Valjean into a head-on collision course. The eventual unmasking of Valjean as an ex-convict causes Valjean to flee with the prostitute's daughter. But Javert will not stop in his pursuit of justice, and he chases Valjean across the country.

Javert is the personification of the state. He is the state's high priest. His unquenchable desire to uphold the law is revealed to be ancient in origin and, hence, sacrificial. Today, many intellectuals speak of the violence of religion, yet very few speak of the violence of the state. The state is very religious, not many dare to recognize this. It operates through the ancient but effective sacrificial mechanism. Scapegoats, violent and non violent offenders, are routinely thrown into cages by the priesthood; this keeps the state in existence, and the catharsis just balmy enough to contain a full fledged all-against-all war. Valjean, on the other hand, is the Christ imitator. He is a priest of the kingdom of God. He is chained to Christ mimesis, and thus cannot use violence and coercion. His only weapon is the crucified life of Christ.

Whereas Javert does not care about a man's potential to reform, Valjean forgives freely. Javert is the law through coercion while Valjean is the law through imitation. One mercilessly throws human beings into cages and the other turns the cheek. The two are, for obvious reasons, irreconcilable.

Javert is finally able to apprehend his man after years of pursuit, but he realizes the superiority of Valjean's law and concludes that he is made directionless because of Valjean's Christ-man. He realizes the immorality of the state's use of violence and the brutal nature of its prisons where countless men languish and are broken forever. The inspector lets go of his man, and commits suicide, marking the obsolete nature of the state in the presence of a viral Christian mimesis.

To this day, thousands suffer in prison. The state-engineered media will echo the violence committed by people, but it will always downplay the violence of the state. Little is spoken of the widespread rape of offenders in prisons across the world. A man guilty of not paying back loans is just as likely to be raped as the vicious murderer. And all this while under the supervision of the state's priesthood. This is the cold reality of governments everywhere.

The state has always been a continuation of religion; violence and coercion has always been it's ritual sacrifice. But this does not mean that we should rise up and rebel against it in a mimetic manner. Such stupidity is reserved for the Marxists and clueless leftists. God revealed to us what we must do while living under the state. His answer is Jesus. This answer is amplified in Victor's Hugo's Jean Valjean. The ex-convict Valjean shows mercy not only to the victims, but also to the oppressors. His form of justice is restorative and does not require scapegoats. He helps out the workers. He practices benevolence towards those who are unfortunate enough in society. He becomes father and protector to an orphaned girl. And he, on more than one occasion, spares Javert's life.

The life of the fictional Valjean is a mirror image of the divine Savior. His life is an excellent example of how Christians must behave under the tyranny of the state. Only a fool would take the state, which makes full use of the scapegoat mechanism, as a moral agent of society. The true moral agent for mankind is and has always been none other than Jesus Christ, and his imitation, and the viral nature of it, renders all government and religious institutions obsolete.